Meeting the Past on the Square

Recently I retired from teaching at a college in Tennessee. A native Texan, I gave way to a recurrent urge I had experienced over the years to return to the places I associated with my boyhood in Hopkins County. I planned a weekend trip and drove from my home in Martin, Tenn., to Mount Vernon in northwest Texas. On a hot, humid day in August I took a room at the new Super 8 Motel.

The next morning I went to the public library to read old copies of the Optic-Herald on microfilm. The Optic-Herald is a weekly newspaper that my parents subscribed to when I was a child growing up in Hopkins County. They have been dead 25 years now, and I wanted copies of the newspaper from the time of their childhood in the first decade of the 20th century.

My next destination was Commerce, 40 miles west of Mount Vernon. After high school I spent four years as a student at what was then called East Texas State College in Commerce. On the way, I wanted to stop in Sulphur Springs, the county seat of Hopkins County.

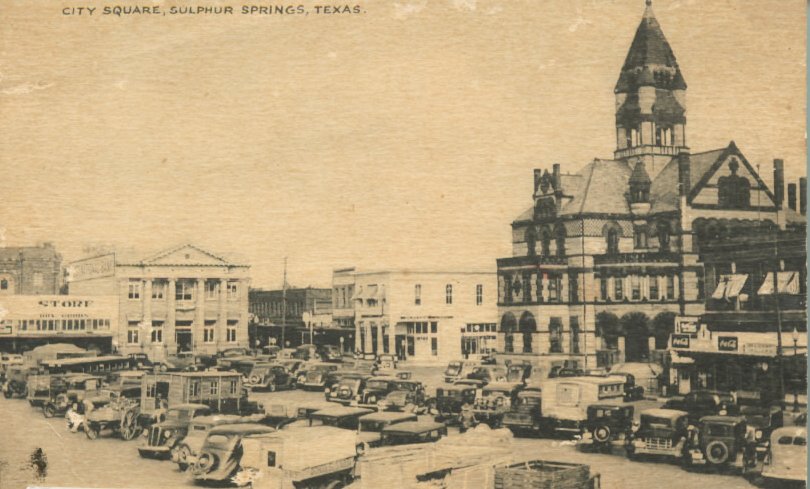

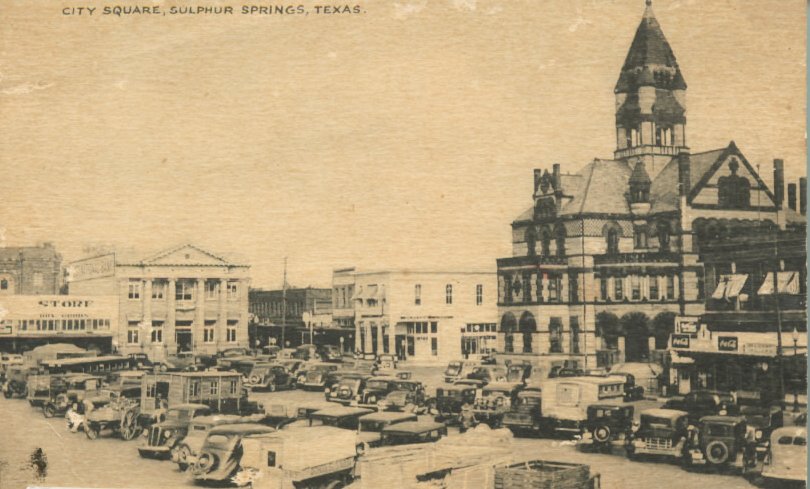

After exiting Interstate 30 I drove to the courthouse square in the center of town. I was curious to see what changes had taken place since I had frequented the square more than 50 years ago. The courthouse, built in 1894 of red granite and limestone, was still there, along with a parking area covered in red bricks that absorbed and reflected the sun's rays. On that summer day the heat made it difficult to breathe.

Hungry and thirsty, I went into the Plain and Fancy

Sandwich Shop on the south side of the square.

I ate a tuna sandwich and drank a tumbler of iced tea

while I admired the red courthouse against the blue

August sky.

One of the many changes I noticed in the square was

the number of drugstores. Instead of the four I

remembered from 50 years ago, there is now only one.

My mother swore that Sterling Drug Store, which

once stood on the east side of the square, served the

best cherry Cokes in East Texas. A farm woman, she

was generally uncomfortable in town, but she felt fine

in Sterling's with a glass of cherry Coke and chipped

ice before her on a little marble-topped table at the back The Sulphur Springs, Texas, Square in the 1930s

of the store. My brother and I often met her there about

2 o'clock after we watched the matinee at the Carnation

Theater.

I realized it had been 36 hours since I said goodbye to my wife and began my trip to Texas. Since then I had spoken to no one I knew. In Martin, Tenn., where I had been working for almost 30 years, I was known as "someone who teaches at the college." Here in Sulphur Springs, the seat of the county where I was born, I was important only to those who saw me as a customer. As I sat alone at the table in the Plain and Fancy, I had an urge to begin conversing with three men seated at another table. I wanted to say, "I used to live near here. I remember when the Carnation Theater stood where that little park with its shrubs and lonely bench now sits." I felt unhappy and uncomfortable realizing that my face was just another stranger's face.

After lunch I went to the Hopkins County Museum, where I found an impressive collection of farming tools from another era. The only other person on the premises was the curator, who had moved to Sulphur Springs from Louisiana only two or three years before. I still felt like any other tourist passing through town.

I returned to the square and entered the only drugstore, hoping to order a cherry Coke. To my disappointment, there was no soda fountain. I decided to return to Plain and Fancy for more iced tea. As I retraced my steps, I thought of another man who had walked many miles on that square. He was Walter Perkins, a prominent Hopkins County resident.

Walter married Minnie, my mother's only aunt on her mother's side of the family. The couple lived on a farm about two miles north of the courthouse. They raised two sons, one of whom became a dentist. The other became a successful businessman in Shreveport, La. After their sons graduated from high school, they spent very little time in their parents' home.

Minnie and Walter were tall, their backs straight even after they reached 60 years of age. They liked to attend community dances when they had the opportunity, though in the predominantly Baptist community opportunities did not come often. I remembered seeing Minnie and Walter dance across the linoleum-covered floor of our sitting room on a Sunday afternoon when they were visiting us and my father had tuned the radio to a station that featured local fiddlers. When she was 80 or so, Aunt Minnie died of breast cancer, leaving Uncle Walter to spend the remainder of his days alone. It was during this period of his life that I saw Walter more often than ever before.

When I was in my early teens and my brother three years younger, we often rode to town with our father in the summers. Daddy was a member of the county's Agricultural Stabilization Committee, and occasionally there were meetings to attend in Sulphur Springs. He had to report to the ASC office at midmorning. This schedule meant that my brother and I had to occupy ourselves until noon, when the weekday matinee began. Humphrey Bogart and Alan Ladd, two of our favorites, were big then.

Before the theater opened we had more than enough time to look at the displays in the five-and-dime stores, the department stores, the shoe stores, and the jewelry stores. We would walk around the square as many as three or four times, eventually stopping at noon at the Carnation Theater, where we were often the first ones to take seats.

At first, when we started meeting Walter sauntering around the square those mornings, we politely answered his questions. "How are you boys?" Uncle Walter would ask. We were always fine, thank you, and our parents were always fine. And the crops were always good, we said, even though our father, had he been asked, could have mentioned the cutworms in the corn or the thistles in the lespedeza crop. It was not unusual to answer the same questions more than once the same morning.

If my brother and I were walking clockwise and Uncle Walter was walking counterclockwise, we were bound to meet more than once. Several of the other old men sat on benches in front of the courthouse or on window ledges at City National Bank, but Uncle Walter preferred to walk.

Soon I began to spot Uncle Walter and his distinctive gait before he recognized my brother or me. I would say,"Let's duck into the drugstore while Uncle Walter passes by." Or sometimes, if my brother spotted him before I did, he would tug my shirt sleeve, pointing to the alley between the dry-cleaning establishment and Sterling's Drug Store while whispering, "Here comes Uncle Walter."

As I strolled the courthouse square that August day, I remembered that Uncle Walter had taken the same route many times. I realized too, that I was approaching the age he had been, when my brother and I began to avoid him.

For a few hours that afternoon I was as lonely as Walter must have been every day those last years of his life. Although my loneliness was temporary and his was ongoing, the parallels between between the two situations teased my mind. Probably no one walking on the square that afternoon deliberately avoided me, but there must have been 30 or more pedestrians who stared through me as if I were invisible. I found myself hoping that somehow I would meet a son or grandson of one of my forgotten Hopkins County cousins. Just as Uncle Walter had a few questions for my brother and me, I am sure I could have thought of a few questions to ask them.

_________________

From the Houston Chronicle Magazine Texas, January 27, 2002. Robert G. Cowser is a retired emeritus professor of English at the University of Tennessee at Martin. He grew up on a farm south of Saltillo and attended Saltillo School.