REFLECTIONS ON THE SIXTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR

By Robert Cowser

Though it occurred thousands of miles from my parents' farm in Northeast Texas, probably the most momentous event of my childhood was the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The sun was shining that December afternoon when the radio announcer reported the news of the attack, though there was a chill in the air. I hardly noticed the chill, however, when I ran to the cow lot to tell my father. He came to the house with me to hear more details.

The following morning the superintendent of the school I attended brought a console radio to the lunchroom so that the entire student body, about 225 pupils, and the faculty of fifteen teachers could hear President Roosevelt address the joint houses of Congress. This is the speech in which the President referred to Sunday, December 7, 1941, as a day "that will live in infamy." As a ten-year-old, I had not learned the meaning of the word infamy, but I knew from the intonation of the President's voice that December 7 must have been an evil day.

Only a year before, in a straw vote conducted in our fourth-grade class by Ruby Blann, the teacher, Thomas F. Dewey had received almost as many votes as Franklin D. Roosevelt. After the declaration of war, however, there was not a classroom in the building that did not display prominently a portrait of FDR.

In January, 1942, the School Board decided to shorten the school term by requiring classes

to meet on Saturdays. The six-day week soon became a pattern for us children, though it

must have been hard on the teachers, especially those women with families to care for. The

school term ended about four weeks earlier than usual. At the end of the school year, the

superintendent, an excellent mathematician, entered the army and became an instructor at

a base near Huntsville, Texas. Just before the term ended, the other members of the faculty

planned a farewell party for the superintendent. It was held in the auditorium and all the

faculty and pupils attended. The faculty had bought the superintendent a yellow gold

signet ring. The small box containing the ring had been placed in the smallest of a series

of boxes. When the superintendent was told that the large box in prominent display on

the stage contained a gift for him, he may have thought it contained a large radio or

phonograph. We in the audience were highly amused to watch him open box after box

before he came to the one containing the ring.

Because the term ended earlier than usual, several other male teachers were able to complete their duties at school and enter the army by the middle of May. Several boys from the relatively small junior and senior classes also went to various branches of the service in May or June. Annie Jo Russell, my pretty fifth-grade teacher, was engaged to a soldier. She had graduated from East Texas State Teachers College the year before. More than once during the spring of 1942, if I had finished my classwork, Miss Russell would allow me to walk the two blocks to the post office in order to mail a letter addressed to her fiance.

Three of the sons of Jim and Delie Young, who lived on the farm just west of ours, served in the Army, the oldest having joined six or eight years before Pearl Harbor was attacked. The other two were drafted early in 1942. To demonstrate our patriotism, their sister Majorie, who was my age, my seven-year-old brother, and I learned the words to "As Those Caissons Go Rolling Along," "Anchors Aweigh," "The Marines' Hymn," and the official song of the Army Air Corps, which begins "Off we go into the wild blue yonder."

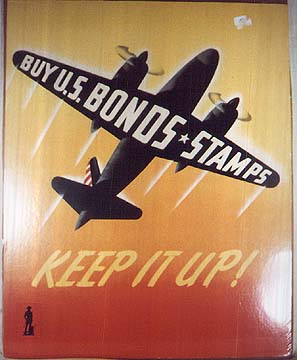

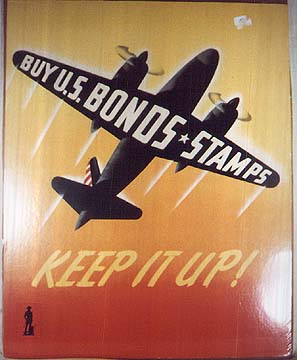

My older sister's husband was drafted early in 1942. Although he was just past thirty years of age, the county in West Texas where he lived could not meet its draft quota without drafting men over thirty in the first wave. He took basic training at a camp near Alexandria, Louisiana, and then was sent to Camp Rucker, now a Fort, in Alabama for further training. He was accepted into Officer's Candidate School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, early in the fall of 1942. Because of a persistent problem with his knee, however, he was discharged in February, 1943. He and my sister bought property from my father and built a house located one quarter of a mile from my parents' house. The government sold savings stamps in twenty-five-cent denominations. Xanthus, my brother-in-law, took my younger brother and me to the post office in Sulphur Springs. He got a book for each of us and bought a set of starter stamps for us. He wanted us to use some of our spending money to complete the book. If we bought $18.75 worth of stamps, then the stamps would be worth $25.00 in a certain number of years -- 10 years, I believe.

The attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent war affected our lives so profoundly it is hard to recall any gathering, formal or informal, small or large, that was not affected by the wartime atmosphere. The prayers in the church services and at school, the lessons in the classrooms, and the conversations among neighbors all reflected the country's concentration on the war.

_________

Robert Cowser grew up on a farm just south of Saltillo, Texas. He is a retired professor emeritus from the University of Tennessee at Martin, Tennessee, and he and his wife live in Martin, Tennessee.